Spacewalk directed by teleoperating a Wi-Fi® connected virtual reality “Space Camera”

Figure 1: Japanese astronaut Akihiko Hoshide is pictured during a spacewalk in this photograph taken by French astronaut Thomas Pesquet. Felix & Paul Studios’ Outer Space Camera is visible between Hoshide’s left shoulder and JAXA's Kibo laboratory module. Source: NASA

Felix & Paul Studios, in association with TIME Studios, have captured footage of a spacewalk using a Wi-Fi® connected virtual reality camera outside of the International Space Station (ISS). Episode 4 of Space Explorers: The ISS Experience, could be released in December.

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) astronaut and ISS Commander Akihiko Hoshide and European Space Agency (ESA) astronaut Thomas Pesquet assembled a mounting bracket that will support a new solar panel planned for the station’s port truss during the extra-vehicular activity on September 12, 2021. Sometimes working in the dark, sometimes in bright sunlight, Hoshide and Pesquet used electric “pistol grip tools” to fasten together a kit of parts, pausing occasionally to torque the bolts, visually inspect gaps, and pull and wiggle to check their workmanship. NASA is introducing the new smaller “Roll-out Solar Arrays” to the ISS to supplement the station’s aging power panels and also to evaluate this newer technology ahead of constructing a Gateway lunar outpost.

Figure 2: Felix & Paul Studios’ Outer Space Camera (left) is positioned behind JAXA astronaut Akihiko Hoshide (lower left foreground) as he assembles a bracket at a worksite on the truss of the International Space Station. Two Wi-Fi antennas are visible at the base of the camera’s tripod. The Wi-Fi antenna below the red stripe on Hoshide’s spacesuit transmits low-rate telemetry from sensors in his suit. Source: NASA

During the spacewalk, a wireless video upstream from nine cameras served as the critical “viewfinder” so the camera operator could control exposure and focus, and the director could see the field of view and lead the filming activity. The sun sets on the space station once every hour and a half and so lighting changes frequently over the course of a seven-hour spacewalk. The camera recorded raw high-definition footage that will be “downlinked” for the production.

Figure 3: A flattened snapshot beneath the International Space Station, taken by the “ISS Experience” virtual reality camera. The first of NASA’s Roll-Out Solar Arrays is visible at left. Source: Felix and Paul Studios and Nanoracks

The footage was shot for the final episode in an immersive series about astronauts’ work and life aboard the ISS. On the evening before the spacewalk, with the camera already mounted on the ISS’ Canadarm2 robotic arm, Felix & Paul Studios was awarded a Primetime Emmy for Space Explorers: The ISS Experience series with all episodes filmed entirely in space inside the living quarters and laboratories of the ISS. The Global XR Content Telco Alliance was among the production’s sponsors.

Figure 4: NASA astronaut Nick Hague prepares a cinematic virtual reality camera for a scene while Canadian Space Agency (CSA) astronaut David Saint-Jacques exercises. Source: NASA

For shooting indoor scenes, Nanoracks engineers modified the camera to remove the reliance on a gravitational sensor for frame of reference. Engineers repackaged the indoor camera to address crew safety requirements (broken glass is extra dangerous in zero gravity), and to match with the space station interfaces. During indoor production, the ground production crew operated the camera through an Ethernet connection.

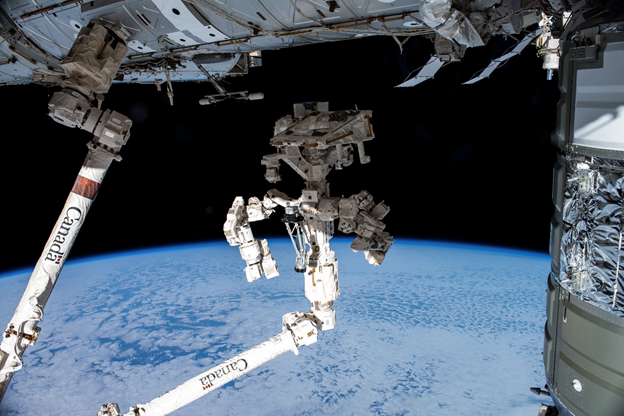

Figure 5: Felix & Paul Studios’ virtual reality camera head is mounted to the Nanoracks Kaber interface on the Dextre “hand” on the Canadarm2. Source: NASA

Nanoracks helped build and qualify a second camera for Felix & Paul Studios to extend the production outside into the environment of space. This camera was ruggedized and repackaged for exterior scenes, with modifications that included a Moxa Wi-Fi wireless Ethernet bridge and an adapter to connect to power and control signals through Nanoracks’ interface to the Dextre “hand” on the Canadian Canadarm2. The arm does not connect to a wired high-speed signaling interface such as Ethernet, although it does provide a MIL-STD-1553 bus for commands and telemetry that need highly reliable delivery. By design, Nanoracks’ Kaber is a MicroSat deployer, and so the camera assembly is in this sense a MicroSat that doesn’t deploy.

Figure 6: European Space Agency astronaut Thomas Pesquet poses in August with Felix & Paul Studios’ cinematic virtual reality camera head that is packaged with Wi-Fi to capture a spacewalk. Source: NASA

In March, Felix & Paul Studios attempted to record virtual reality scenes outside the ISS. Four days in advance of a spacewalk, the crew loaded the camera assembly into the Japanese airlock. Once out of the airlock, the camera and Kaber assembly was grappled by the Dextre robotic manipulator “hand” mounted on the Canadarm2 robotic arm. However, the camera did not respond to commands that should have powered it and had to be brought back inside. A new “bypass” power cable had to be designed, built, tested, and manifested for launch to the ISS to address this issue. An August launch carried the cable adapter to the space station. The adapter arrived eight days before a scheduled spacewalk, and with five months until the next opportunity, the crew quickly installed it onto the Kaber. The crew placed the camera back into the airlock, controllers transferred it back outside onto the arm, and the production crew began filming some scenes ahead of the spacewalk. The spacewalk then needed to be postponed for medical reasons, with astronaut Mark Vande Hei foregoing the opportunity because “today just wasn’t the right day.”

The filming location was a challenging one for Wi-Fi because of the concentration of upstream video clients and the range to the nearest access point. The film crew demanded a stable network connection as any loss of signal resulted in the inability to modify the manual camera settings as the lighting changes quickly. Operators employed legacy systems to supplement bandwidth. Two pan-tilt assemblies mounted near the worksites supported camera clusters, each with a wired legacy standard-definition analog camera and also a Wi-Fi connected high-definition camera.

In March, NASA astronauts Victor Glover and Michael Hopkins routed two Ethernet cables onto the station’s port-side truss. These cables would eventually connect the two wireless cameras as wired access points and wired cameras that will eventually build out Wi-Fi coverage while also offloading wireless traffic. However, to offload the traffic during the filming, operators relied on the legacy standard-definition wired analog video. Additionally, the ISS crew has recently installed a high-definition wireless helmet camera in each of the spacesuits. Each suit also has a Wi-Fi connected low-rate telemetry recorder. These two Wi-Fi mobile clients have a dynamic connection speed. In the interest of network stability, ground controllers configured the pair of high-definition helmet cameras to record without streaming and the support team relied instead on the legacy analog standard definition helmet camera during the activity and then upstreamed (NASA says “downlinked”) the video to the ground after the astronauts had returned inside.

NASA’s Wi-Fi CERTIFIED™ infrastructure on the space station accommodated every camera position that the production team asked for. Among all of the obstacles that the ISS Experience production team had to overcome to achieve the ambitious capture of a spacewalk in virtual reality, wirelessly connecting to a commercially available camera head product from the ground through an Internet Protocol network was one of the least distracting. Having the option to use a Wi-Fi interface was important for turning a far-out vision into a reality.

Trade names and trademarks are used in this report for identification only. Their usage does not constitute an official endorsement, either expressed or implied, by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

The statements and opinions by each Wi-Fi Alliance member and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions or views of Wi-Fi Alliance or any other member. Wi-Fi Alliance is not responsible for the accuracy of any of the information provided by any member in posting to or commenting on this blog. Concerns should be directed to info@wi-fi.org.

Add new comment